Methamphetamine—better known as meth—is often portrayed in dramatic before-and-after photos or in stories of rapid physical decline. But behind the gaunt faces and scarred skin lies something even more devastating: the way meth alters the brain.

Table of Contents

ToggleFar beyond just “getting high,” meth causes deep, lasting changes in brain chemistry, function, and even structure. These changes affect everything from memory and emotion to decision-making and impulse control—and in many cases, they don’t go away when the drug use stops.

If you or someone you care about is using meth, understanding how it impacts the brain isn’t just interesting—it’s essential. In this post, we’ll take a close look at what meth does to the brain, why it’s so neurologically dangerous, and what recovery really looks like. Because the more we understand, the better equipped we are to heal.

Meth and the Brain: A Toxic Relationship

Methamphetamine is a synthetic stimulant that targets the central nervous system. It works by increasing the amount of dopamine in the brain—a neurotransmitter involved in pleasure, movement, attention, and motivation.

But while natural dopamine release is a tightly regulated process, meth hijacks the system. It causes the brain to release up to 1,000 times more dopamine than normal. This produces the intense euphoria users crave—but at a high cost.

Over time, meth use damages the very systems that produce and respond to dopamine. The brain becomes less able to experience pleasure naturally, leading to an emotional crash that drives further use.

The Neurological Domino Effect

Meth doesn’t damage just one part of the brain—it impacts multiple systems at once. The result is a cascade of neurological consequences that affect nearly every aspect of thought, feeling, and behavior.

Let’s break down the main areas meth affects:

1. The Prefrontal Cortex: Decision-Making and Impulse Control

This area helps us weigh risks, plan for the future, and regulate our behavior. Meth use reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex, making users more impulsive and less capable of making sound decisions.

Symptoms of damage:

-

Risky behavior

-

Poor judgment

-

Compulsive drug use

-

Trouble setting and achieving goals

2. The Limbic System: Emotion and Memory

Meth severely disrupts the brain’s emotional center. Users often swing between rage and numbness, joy and despair—sometimes within hours.

Symptoms of damage:

-

Heightened aggression

-

Paranoia

-

Emotional flatness

-

Memory lapses

3. The Striatum: Movement and Reward

Overactivation of the striatum is linked to the hyperactive, repetitive behaviors meth users often display—like picking at skin or obsessively cleaning.

Symptoms of damage:

-

Restlessness

-

Compulsive behaviors

-

Cravings

-

Reduced ability to feel rewarded by everyday activities

4. The Hippocampus: Learning and Long-Term Memory

The hippocampus helps convert short-term experiences into long-term memories. Meth shrinks this area of the brain, impairing learning and recall.

Symptoms of damage:

-

Forgetting conversations or appointments

-

Trouble learning new information

-

Confusion and disorientation

The Myth of “Just Once”

There’s a dangerous myth that using meth once or twice is harmless. But studies show even short-term use can cause changes in the brain.

According to a 2020 report in Nature Neuroscience, one dose of meth can spike dopamine to neurotoxic levels, initiating inflammation and oxidative stress. This begins the process of neuronal damage that gets worse with continued use.

In other words, the first hit starts a biological chain reaction. It’s not just psychological—it’s cellular.

Mini-Story: Luis’s Experience

Luis, a 34-year-old electrician, first tried meth at a party. “I was just curious,” he recalls. “I didn’t think it would affect me like that.”

Within a few weeks, he noticed memory problems. He’d forget tool names, lose track of jobs, and miss deadlines. Six months later, he was fired.

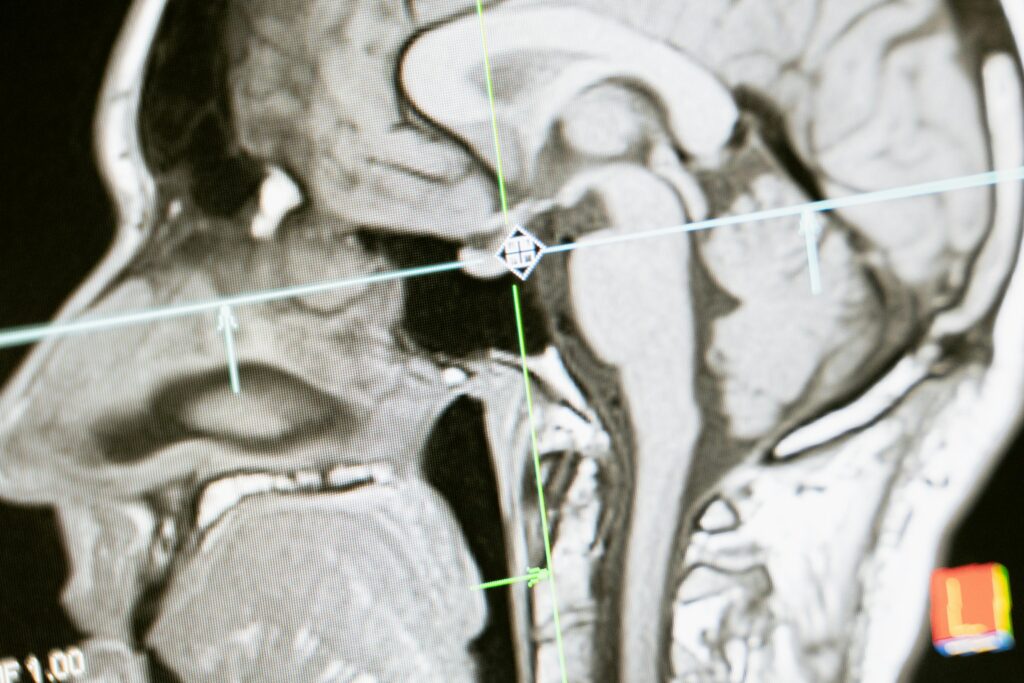

A brain scan revealed reduced gray matter in his frontal lobe and signs of neuroinflammation. With treatment, Luis is now two years sober—but still struggles with short-term memory and emotional regulation.

Why Meth Is Especially Harmful Compared to Other Drugs

All addictive substances affect the brain—but meth hits harder and leaves deeper scars. Here’s why:

-

It lasts longer. A single dose of meth can remain active in the brain for 8–24 hours.

-

It overstimulates. Meth releases far more dopamine than cocaine or heroin.

-

It’s neurotoxic. Meth damages neurons directly, especially dopamine and serotonin receptors.

-

It creates behavioral loops. Meth users often engage in repetitive behaviors, increasing risk of injury and psychosis.

A 2022 review in Frontiers in Psychiatry found that meth users showed greater deficits in cognitive flexibility, attention, and emotional recognition than users of other stimulants.

Psychosis and Hallucinations: The Mental Toll

One of the most alarming effects of meth on the brain is its ability to trigger psychosis—a break from reality. Many users experience:

-

Visual hallucinations (seeing people, lights, or animals that aren’t there)

-

Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices or noises)

-

Paranoia (believing they’re being watched or followed)

-

Delusions (irrational beliefs, like thinking they’re being poisoned or that their thoughts are being broadcast)

Up to 40% of long-term meth users develop psychotic symptoms, according to the Journal of Addiction Medicine. In some, the symptoms resolve with abstinence. In others, they persist for months—or become permanent.

What Brain Scans Reveal

Imaging studies give us a window into meth’s damage. MRI and PET scans of chronic users show:

-

Reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus

-

Inflammation in areas involved in mood and cognition

-

Lower dopamine receptor density, even after a year of sobriety

-

Ventricular enlargement, a sign of brain tissue loss

In short, the brain physically shrinks in critical areas. This isn’t just “brain fog”—it’s neurodegeneration.

Recovery Is Possible—But Not Instant

The brain is resilient. With time, some of meth’s effects can be reversed. But healing isn’t automatic, and it’s rarely complete.

Studies show that:

-

Motor function begins improving after 6–12 months of abstinence.

-

Memory and emotional regulation may take 1–2 years to show measurable gains.

-

Dopamine receptor levels remain lower than normal even after 14 months of recovery.

The good news? Treatment accelerates healing. Behavioral therapy, nutrition, sleep, and social support all promote neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire itself.

What Withdrawal Looks Like

When a person stops using meth, their brain struggles to rebalance. Common withdrawal symptoms include:

-

Extreme fatigue

-

Depression or suicidal thoughts

-

Intense drug cravings

-

Confusion and irritability

-

Sleep disturbances

This phase can last 1–2 weeks—but some symptoms, especially mood swings and concentration problems, linger for months. That’s why supervised detox and long-term care are so important.

Comorbid Conditions: Meth and Mental Illness

Meth use doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Many users also struggle with:

-

Depression

-

Anxiety

-

Bipolar disorder

-

ADHD

-

PTSD

For some, meth is a form of self-medication. For others, the drug triggers dormant conditions. In either case, integrated dual-diagnosis care is essential.

A 2023 SAMHSA report found that 49% of individuals with meth addiction also had a diagnosable mental health disorder. Treating both issues together yields the best outcomes.

The Role of Neuroinflammation

Emerging research points to neuroinflammation as a major factor in meth-related brain damage. Meth increases inflammatory cytokines in the brain, which:

-

Damage neurons

-

Impair synaptic connections

-

Hinder recovery

-

Increase risk of mood disorders

Anti-inflammatory strategies—like omega-3 supplementation, exercise, and certain medications—are being explored as ways to support brain healing.

Can Medication Help?

There’s no FDA-approved medication for meth addiction (yet), but promising options are emerging:

-

Bupropion: An antidepressant that may reduce cravings

-

Naltrexone: Often used for alcohol or opioid addiction, now being tested for meth

-

Modafinil: A wakefulness agent that may help with attention and energy

-

Antipsychotics: Used short-term to treat hallucinations or severe paranoia

Medication alone isn’t enough—but as part of a broader recovery plan, it can be transformative.

Case Study: How Renew Health Supports Brain Recovery

At Renew Health, we’ve seen firsthand how comprehensive care can help people reclaim their cognitive abilities and emotional balance.

One client, Nicole, came to us after a decade of meth use. She couldn’t focus for more than a few minutes, struggled with depression, and experienced frequent flashbacks.

Over 18 months, Nicole engaged in:

-

CBT and trauma therapy

-

Virtual psychiatry appointments

-

Nutritional support

-

Cognitive training exercises

-

Group therapy and peer support

Today, she’s rebuilding her career and parenting her children with renewed confidence. Her brain didn’t just survive meth—it began to thrive again.

Actionable Takeaways

-

Meth causes profound changes in brain chemistry and structure—especially in regions linked to emotion, decision-making, and memory.

-

Damage includes reduced gray matter, neuroinflammation, and disrupted dopamine pathways.

-

Even short-term use can cause neurological harm; long-term use increases risk of psychosis, cognitive decline, and emotional instability.

-

Brain recovery is possible, especially with the right mix of therapy, support, nutrition, and time.

-

Integrated treatment programs that address both addiction and mental health are essential to long-term success.

If you’re wondering whether the brain can bounce back from meth—the answer is yes. Not easily, and not overnight. But yes.

Renew Health: Your Partner in Meth Brain Recovery

Phone: 575‑363‑HELP (4357)

Website: www.renewhealth.com